Advertisement:

Read Later

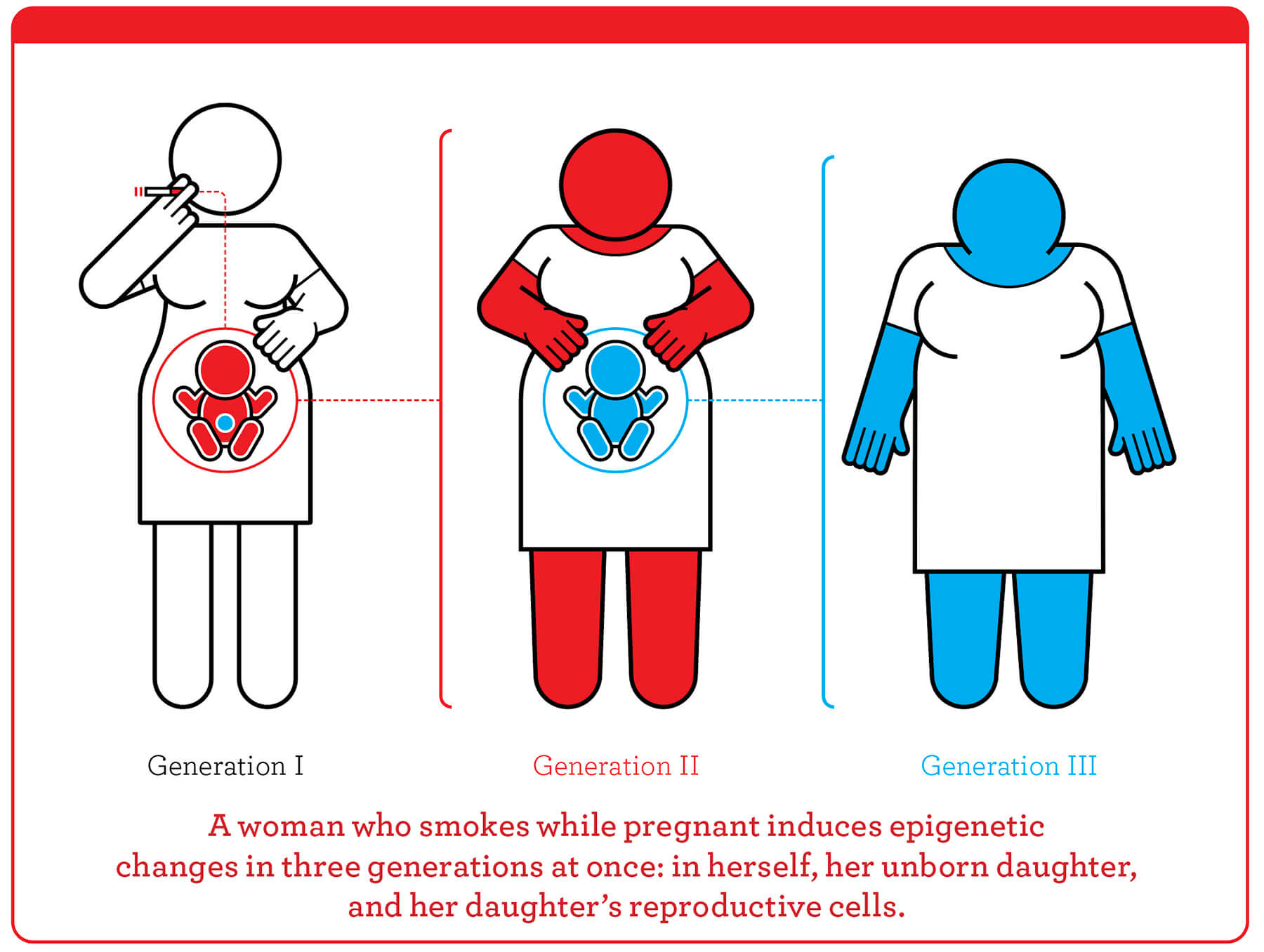

In this article series named ShortCut, I share some interesting and intriguing information elucidating various subjects from the books I have read. In this particular article, I wanted to discuss how what we eat, the air we breathe, and the emotions we feel might alter not only our genes but also our descendants' genes.

"Plant scientists got their first clues to this extra channel of heredity in the mid-1900s. Corn kernels took on new colors, but their offspring did not follow Mendel's Law, and after generations, the ancestral color sometimes returned. A careful inspection of corn DNA showed that these changes to their color were not the result of mutating genes. It was the pattern of methylation that was changing. Each time plant cells divide, they rebuild the same pattern of methylation on the new copies of DNA that they make. But now and then, plant cells alter the pattern: They add an extra methyl group where none was before, or a methyl group falls away and is not restored. These changes can silence a gene in a plant or allow it to become active - triggering, among other things, new colors in corn kernels.

The biology of animals may offer less of an opportunity for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance than that of plants. But that does not necessarily mean it might not.

As our epigenetic focus has sharpened, old assumptions have turned out to be wrong. In 2015, for example, Azim Surani, a biologist at the Wellcome Institute in England, led one of the first studies on the epigenetics in human embryonic cells. In particular, he and his colleagues examined the cells that were on the path to becoming eggs and sperm. They observed these so-called primordial germ cells stripping away most of their methylation before applying a fresh coat. But a few percent of the methyl groups remained stubbornly stuck in place on the DNA.

A lot of the cells shared the same resistant stretches of DNA that held on to their old epigenetic pattern. These stretches contained virus-like pieces of DNA called retrotransposons. They can coax a cell to duplicate them and insert the new copy somewhere else in the cell's DNA. Methylation can muzzle these genetic parasites.

Retrotransposons typically sit near protein-coding genes, and those genes may get muzzled, too. Surani and his colleagues found that some of the genes near the stubborn methylation sites have been linked to disorders ranging from obesity to multiple sclerosis to schizophrenia. Based on their experiments, the scientists concluded that these genes are promising candidates for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance(1)."

(1) Zimmer, Carl. "Flowering Monsters." She Has Her Mother's Laugh: The Powers, Perversions, and Potential of Heredity.. London: Picador, 2018. 438 - 442. Print.

Figure - 136.1 https://harvardmagazine.com/2017/05/is-epigenetics-inherited#22046